I have something of a contrarian streak and also receive compliments poorly, teetering in my head like I’m about to fall off a ladder.

That said, my writing group used to regularly compliment my ability to write realistic dialogue. It was consistent enough that, as a challenge, I wrote one piece that had no dialouge.1

I always enjoyed talking about writing dialogue and would suggest dialogue tweaks when I thought they would be useful. Although I must have told the story in this post more than once, I doubt anyone in the group would have followed how I think I found writing dialogue fun.

Step 1: Secretly Record Conversations With Trusted Friends

I took a reverse track to get there.

A Writer’s Digest book suggested recording conversations to help understand how people actually talk. This will improve your dialogue. I don’t think this is good advice and may fuck up your dialogue. People are incapable of saying what they mean. So how do you create characters who have more to say than there’s time to say it?

I didn’t know any of that at the time. And had a mission. Luckily my Dad’s a journalist and had a microphone for phone interviews when we still had landlines or cordless phones. It used a pickup coil microphone that stuck to the earpiece with a suction cup like this:

After a few minutes I’d forget the suction cup was on and be normal. I recorded about 12 hours of calls that were regular conversations over several months.2 I learned how incomplete we are during the life of a discussion even though we are trying to be as clear as possible. Both/All parties have thoughts to finish; or just rephrase something a bit better. The result is stammering, rephrasings, interruptions, and all sorts of imperfections in the pursuit of trying to say what you mean.

These imperfections make us human and why conversations can suck but also what make characters interesting in fiction. I heard these patterns in conversations all the time after I started listening to my sneaky recordings. Everyone was trying to be as clear as possible yet speaking in halts and umms and backtracks and contradictions.

Step 2: The Film’s English

Most books and film smooth out conversations from the mess it really is. Smoothed over dialogue establishes the milieu of a business world; delivers crutial plot information about what motivates an iconic villain; and allows a character to share why past Christmas horrors make this Christmas even worse than she could have ever imagined.

Characters in film and fiction usually spoke more completely than we do in actual conversation because the writers are doing several things at once. The dialogue is in service to a mix of setting, story, suspense, character, etc.

Unrealistic dialogue, especially in film, made my antanne twitch. Too-perfectly composed thoughts in tense or emotionally fraught scenes took me out of a story. I wanted to write characters who spoke like human beings without seeming like a mess of sputtering assholes.

Then Glengarry Glen Ross was adapted for film.

David Mamet’s dialogue opened a new way of approaching the assholes problem. It’s not realistic but has the cadance of imperfect people, thinking while they speak.

Some Film Blab:

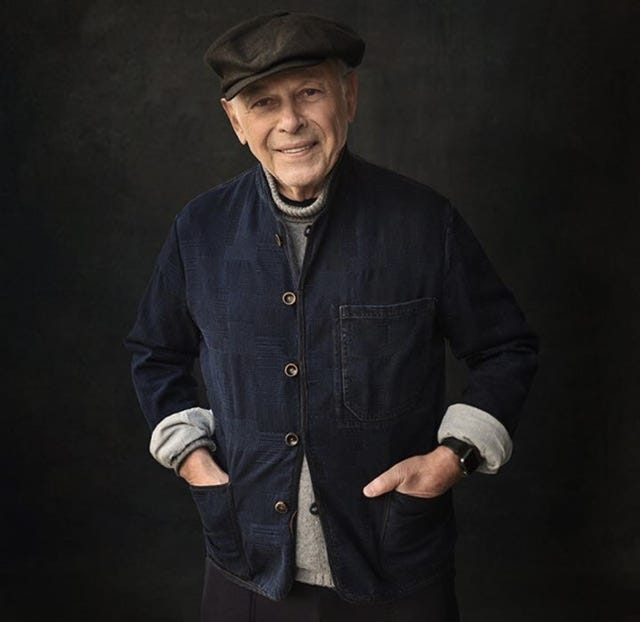

I think the adaptation of Glengarry Glen Ross stood out because characters with authority (Alec Baldwin’s “Blake” and Kevin Spacey’s Williamson) have composed monologues. Baldwin’s character was added for the film and verges on self-parody, given that he brings a pair of brass balls with him as a kind of show-and-tell to salesmen he has belittled and lectured about how to be real men. Ripe.

Spacey’s smarmy manager-of-men creature has a one, vicious moment. A verbal shiv in Shelley’s (Jack Lemmon) gut—the one-time star salesman—when he’s at a low point.

The film hasn’t aged well but Spacey’s character seems ok. He’s a creature who has had lines banked for a while to hurt someone more skilled than him.3

Perfect dialogue in film and the messy way we actually speak created a challenge for trying to write dialogue I liked reading: I had to keep in mind what the speaking chatacter was thinking but not saying, because who they are as a character was somehow in the way.

It’s almost impossible for a person to say just the right thing at the right time. I may have done it once.

A character who can’t find the right words in time; doesn’t undertstand themselves fully; mispeaks is relatable. Knowing what characters what to say but can’t fully express creates a “gravity.” Thinking about it as a kind of physics, then spy and romance novels share the same principle. Example: two characters (spies or lovers) in a taxi with a few minutes for one to slip the other a truth in a jumble of words about the city passing by before they get out.

There’s tension because the reader knows there’s more unsaid and what’s unsaid draws them into the scene. It’s exciting for me to write, because it’s the kind of thing I’d want to read.

Witholding or miscommunicating developed into an important gear I’d use in dialogue to show character; build a story’s steaks and just make it fun to write a first draft.

Talking About Dialogue With Writers

I didn’t feel like a one-trick pony when my writing was frequently noted for interesting dialogue. First draft dialogue was fun. Feedback would also push against what had just felt fun to write and create tension. A character hadn’t come across like I expected or the scene was misleading. The cost of not being able to say everything is early readers misunderstand.

Writing groups and trusted friends allow space for finding out what works and it helped me refine characters when I asked what was learned about them from scenes without dialogue.4

I’m finding the voices for a long thing—going back and forth between a novella and novel. I found two words of Rhode Island slang in an interview Conan O’Brian did with Charlie Day that brought one to life. Voices come from wild places.

I try to think about the world I’m trying to create since my characters will talk in it: I save pictures that stand out to me as soon they’re there; I save overheard phrases; highlight passages in novels, articles, etc; and jot down ideas that seem like they’ll be useful later. Nothing great but it builds the world.

They make quinoa using shit? Manure, or whatever.

— Overheard about a salad I order regularly.

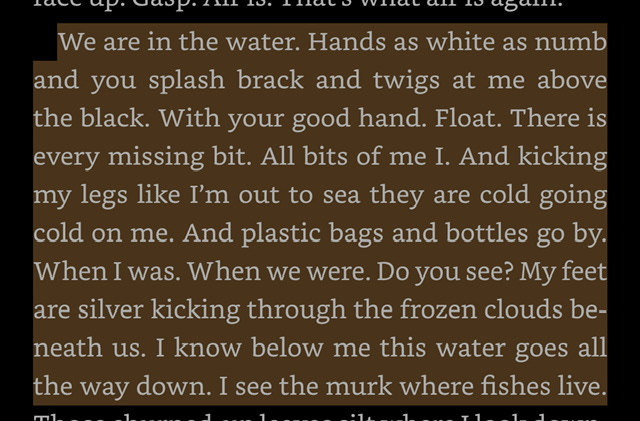

A sister & brother adrift! From A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing by Eimear McBride5 (2017):

“Charlie Day on Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend: fam member says “clean” when he means something good and “suspect” for not good.

‘Inception. Yeah, that one’s clean.’ Takes a drag of his smoke, ‘Some of his others? What’s it? The Tentants?’ Points the Marlboro at N. ‘Suspect.’” (link)

Thanks for reading.

_pmc

I remember one, because it was a ghost story and the feedback was aimed at settings, descriptions and specific details that was all useful. I felt like going back to that story with colder eyes after a few months. Probably worth reviewing now.

Years later, I saw another writer in my family casually setting an iPhone on a table or their leg when a discussion got dramatic. The same advice about recording had been doled out from another source. I think there’s more to learn from how people speak when they’re telling a story or trying to say what they think than a big boom. But yes, both are creepy.

Dated films are worth watching. These characters are talking and thinking. The performances Jonathan Pryce, Jack Lemmon and Alan Arkin give run the game. It’s a travesty of bravado and fraility but always a gripping watch.

This can be a hard ask during a group. A way I found to self-check this is to print the piece and tape it to the wall and look at where all the dialogue is. Characters who talk too much are immediately comparable to ones who talk too little. Review the pages without dialogue and think about why they don’t speak.

If you’re only ever going listen to one novel as an audiobook…

It’s interesting to think about Glengary Glenross with respect to dialogue. The professions it showcases (sales & to a lesser extent management) rely on dialogue to make their daily bread yet writing or the profession of writing is often solitary. I’m reminded of a salesman scoffing at the complement of being called a “natural salesman”. He scoffed because it ignored all of the hard work it took for him to get good at his craft.

With dialogue and the writing of dialogue, I wonder how writers consider the conversation they are also having with their reader. Beyond the characters and plot, how do writers feel about the meta-conversation they are having with their readers?

Thanks for the Blab!